C.V., interviews and writings

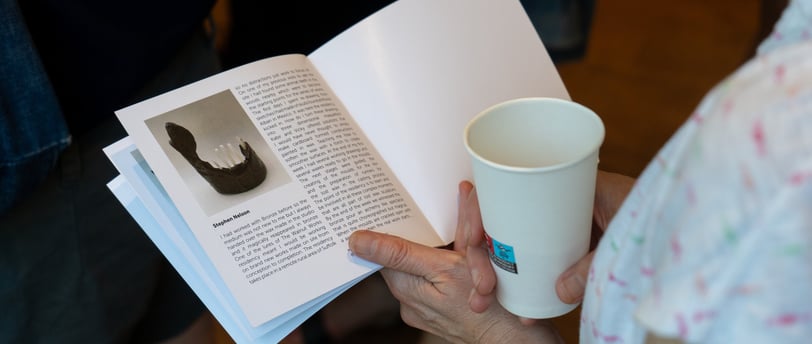

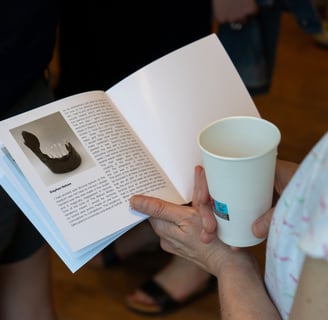

Discover the captivating portfolio of artist Stephen Nelson. Dive into the world of creativity and inspiration that defines Nelson's artistic expression and legacy in the contemporary art scene. Scroll down for texts by Gilane Tawadros and Martin Holman.

21 min read

Curriculum Vitae

Education

1983-84 Masters Fine Art, Birmingham

1980-83 B.A (Hons) Fine Art, South Glamorgan Institute

Awards

1984 Fellowship in painting, Cheltenham College of Art

1990 British Council Travel Award

1999-2000 Arts Council England Helen Chadwick Fellowship at the University of Oxford and British School at Rome

2019 Artist in residence, Hogchester Arts, Dorset

Solo Exhibitions

2022 Little Wretches, Ken Art Space, London

2015 Skin falls apart, Francesco Panteleone, Palermo, Italy

2013 Project 1, Contemporary Art Society, London

2008 It’s a soft hard world, Space Station 65, London

1996 Tepuis, Camden Arts Centre, London

1994 Wax, Adam Gallery, London

1993 Bronze, Mario Flecha Gallery, London

Selected Group Exhibitions

2024 Guest artists (Walnut Works), Both Gallery, London

2023 Royal Academy Summer Show, London

Tipping Point, Bell House, London

Italian Effect, Istituto Italiano di Cultura, London

2021 Supernova, Blyth Gallery, Imperial College London

A Matter of Soul, ASC Gallery, London

2020 New Doggerland, Thameside Studios, London

2019 Backyard Sculpture, Domo Baal, London

2017 Poor Art/Arte Povera [also curator], Estorick Collection, London

2016 Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, Royal Academy, London

2014 What Marcel Duchamp Taught Me, The Fine Art Society, London

Bad Copy, curated by Janette Parris. Cardiff Story Museum, Cardiff

2012 No Now, Space Station 65, London

2009 Creekside Open, selected by Jenni Lomax, APT Gallery, London

2008 Walls have ears, Man&Eve, London

Artfutures, Bloomberg Space, London

2006 Like Water, Sartorial Fine Art, London

2005 Thy neighbours ox, Space Station 65, London

2003 100 Drawings, Drawing Room, London

2002 150 Years, University of Gloucestershire,

2001 Stormy Weather, David Lusk Gallery, Memphis, USA

2000 And then there was bad weather ,WLF. London

A different kind of show, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London

Lowarch, Nelson, Walsh, The British School at Rome, Rome, Italy

Emporio Maraini, Istituto Svizzero, Rome, Italy

1999 Stick, Touring Exhibition, Winchester

Chanzo, National Museum, Tanzania

1997 Musee Imaginaire, Museum of Installation, London

Six British Artists, Teatro Asmara, Eritrea, curated by Stephen Nelson

1995 Konrad Lorenzo’s Duck, Lanificio Bona, Turin, Italy. Featuring Maurizio Cattalan, Helen Chadwick, Matt Collinshaw, and Nicky Hirst, curated by Paola Piccato

1994 Group Show ,Hales Gallery, London. Including Lucia Nogueira , Keith Wilson, Richard Woods.

Curators Egg, Anthony Reynolds Gallery, London

INTERVIEW WITH STEPHEN NELSON (in Gilane Tawadros, Life is More Important than Art, Ostrich, 2007)

GILANE TAWADROS: Looking at your works here in the studio, it strikes me that the kind of work you make wouldn’t fit easily into the kind of exhibitions and biennales that currently dominate the contemporary art world.

STEPHEN NELSON: I was reading an article by James Moores, who created the A Foundation in Liverpool, and he says that the conceptual process has almost turned into a litigation about meaning. So the conceptual process has become about trying to transcribe meaning. But my work’s not about that at all; it's about other things that can't be transcribed into text.

GT: This raises the question of the uniqueness of visual arts practice, and the proliferation of video and photographs in biennials and large-scale art exhibitions, and related to that is the development of thematic frameworks for putting artworks together, that don't derive from the process of making or the motivation to make work. And I wonder whether this is something to do with the uniqueness of visual arts practice?

SN: There's nothing wrong with those exhibitions you're talking about but in the case of this year’s Venice Biennale certainly in the Arsenale and to some extent in the Giardini section, what I saw was a kind of reportage. Maybe it's deeply old-fashioned but I think Paul Klee says more about the Maghreb or North Africa than any of these photographs do. And, you know, we are so sophisticated now: I can go on the web and I can watch direct links from Ramallah or Beirut; and if artists are going to delve into that world, in this huge world of communication, I think we have to be slightly more prescient, create something more problematic to look at, and maybe we sit in opposition to reportage. I'm thinking of a place that can't be defined through text. We could make things that have other qualities, in the way that poetry does, although I wonder if that's where we are, and I think it's really strange that the kind of work that I make has lost its way a little, or appears to have lost its way, because it doesn't fit into a brief.

My partner Katherine said to me last night, referring to Lollop she said every time she sees it - and she wasn't being overtly poetic - she said it makes her contract a little.

GT: Which one is Lollop?

SN: Lollop is the one in the corner that's sort of forlorn.

GT: Yes, slightly deflated.

SN: And I said, "What do you mean?" and she said, "It makes me think of time spent in the corner of the classroom." That's the kind of quality I want: I would like somebody’s heart to contract a little, to flutter a little.

GT: I want to go back to what you were saying, because I think what you say is very important for an understanding of your practice and those of other artists too. There is a paradox in the situation in which we find ourselves now. In one sense, the public forms of communication, media and so on, are no longer adequate; they are failing to represent experiences and ideas, and perhaps that's one reason why artists increasingly, and curators too, have been drawn to fill a gap that's emerged, a silence in terms of what's shown and represented. On the other hand and this is why it's paradoxical for me I do think that one of the great qualities of visual art practise is that it can record ("record", not "document") or register things that traditional documentary materials, films, literal documents, are unable to do.

SN: There’s a narrative of construction and experience in these works. I'm deviating from your point a bit, but I think that that might be the place that we need to mediate, and I wonder if it's through the texture of things, the texture of weakness, the texture of experience, that can't be constructed through what we would see.

GT: There's an otherness, an alterity in your work which derives precisely from what you were talking about: the poverty of materials, their found quality, the incidental nature of the materials and objects that you assemble in your work, but also the lack of narrative. Looking at these objects in the studio, it's quite hard for me to find a hook or easy narrative.

SN: I first fell in love with Arte Povera because of this quality of what one could do with the lost world, the thrown-away world, you know, which is how we're constructing the world now. What can we do with this carrier bag? What can we do with this sack or with the texture of that? I'd never realised that Arte Povera was linked to 1960s and 1970s politics. I didn't realise that it was referring to the fabric of Italy as well. I'm interested in that period, in people like Penone or Kounellis to some extent, in the texture of their work, created through material and building and process.

GT: What we're talking about are not signs or symbols which tell a story in a linear, sequential way: we're talking about extrapolating narrative from the materials, from the experience of looking, walking around, touching even.

SN: We've held the bronze wolves here in the studio and talked about weight. I want those ideas, of lightness and weight, of fragility, texture and collage - these words to me still have a ring of poetry about them.

GT: You've made these beautiful wolves; some of them are in wax and a very small number are in bronze. They invite your touch and they provoke an emotion when you hold a wax wolf and a bronze wolf. There is such a difference in their weight, their texture and quality. There's a sense of fragility in both of them, surprisingly enough, a sense of extinction, of something very precarious as well. The wax feels like it might break in my hand.…

SN: It will; it could very easily.

GT: And the bronze feels like something which you had to make in bronze because otherwise it might disappear.

SN: The aim of the Space Station gallery is to have an affordable range of art, so they asked me to come up with an idea for an object that could be sold reasonably, at a price people could afford, and I've been working on wolves since I did the Helen Chadwick Fellowship in Rome. My own brief was to look at wolf behaviour, and so I studied that for about eighteen months, and I made a piece that's never been shown before, and it's about the display behaviour of wolves, about posture and recognition and fear and danger and all the emotive ranges that a wolf will go through physically, or reacting with another pack member, and so on as well as behavioural things like submission, aggression, tail between legs, tail out, tail up, tail wagging, and so on. So I wanted to animate this, and I did it through these wax wolves. But to go back to your point, they do have that fragility, and there is a sense in me, and there's an artistic sense as well, to cast in bronze for longevity or for another place, and it's not unusual for artists to do that. I'm a big fan of Medardo Rosso, who often couldn't afford to cast, so now when you see his work, they're all these beautiful fragile wax things that have been preserved for 120 years or so. It's funny that the wax has a quality that bronze can never have, just like a fingerprint, a touch, a memory. You can't get that in bronze because as soon as you make something permanent you change the nature of what the artist was trying to achieve in some ways. So here you've got a balance of both, and they are completely fragile. They're sort of bespoke toys by any other name.

GT: What attracted you in the first place to wolves?

SN: When I went to Rome to visit, I went to see an artist called Terry Smith who was there, and I was struck by the relationship between the Bioparco (which is a new name for a zoo) where they had a pack of wolves, and a dog park, no less than 10 metres away, where people walked their dogs. I was struck by the irony of these beautiful animals in captivity and all the dogs that had come from wolves out there prancing around with their owners. And you know, the she-wolf suckled Romulus and Remus, so that the symbol of Rome is a wolf, and I just thought there's something in that, that kind of behavioural aspect plus the relationship of Rome to the wolf and the history of the wolf, and I thought that would be a good subject. Also, you had to tie your research into something that you could do at Oxford, at the university, and I thought if I could tie it into the zoology department and look at animal behavioural patterns, somehow I might learn something. And I did, I learnt a lot.

GT: You made a film…

SN: I made two or three videos, sort of semi-constructed. Two are completed. I've exhibited one and I took photographs, because these were the tools for research. I could be on the move and record. I drew as well and I did go to the mountains and track wolves. And the camera and the video camera were things I'd never really used, so they became these new, useful tools to me.

GT: Earlier this year, your studio was full of sculptures made from different materials including a whole series of works made from pipe cleaners. Here today there are a number of different sculptures made from found objects, wood, mixed textiles as you say, there's a collage of paint, tissue, all kinds of things ¾ but there is always also an element of things which are precious that coexist in your work with these poor materials.

SN: These new works are a strange juxtaposition of fabrics and collected things. On my travels I've bought or been given Armenian table mats, Venezuelan fabrics, horse hide from Kazakhstan, so these are all little facets of my travels that are placed into the work, and they're physically placed in the work in the way that William Boyd might write about an experience in Africa. The precious quality in some of the things, by placing them in the work, releases me a little from the hoarding, from the collecting. It’s slightly cathartic too, to imbue them and position them in the best place I can.

GT: You've spoken to me before about this idea of pushing your work. You will work on a piece, develop it, add to it, and then push it over the edge. Can you talk a bit about that and what that means for you?

SN: There are artists I admire and I know who want to get beyond themselves that's the nature of the practice in some ways, to go beyond yourself, to place yourself in a position that can be physical, in some ways it can be intellectual, or to place yourself in a place where you just do not expect to be, or to create something that is beyond your realm of understanding and beyond what you see around you. Now that's not always the easiest thing to do. I mean, we'd all like to wake up one day and paint Caravaggio's St Matthew cycle, things that just shock, shock cities, shock the world. But it's about getting yourself to a point where you feel comfortable and then pushing the "envelope” to achieve the next place.

GT: I don't think you mean shocking in the sense of sensationalist or provocative, do you?

SN: No, no, it's not that. It’s a strange conundrum that the terms we use for "shocking" now are, as you say, to do with a slightly media-induced frenzy. It's the wrong term. "Problematic" is a better term.

GT: Disturbing? A disturbance?

SN: It still implies the chessboard killer; it implies things that shock us in our existence.

GT: Uncomfortable? Is it the opposite of Matisse’s idea that art should be like a comfortable armchair?

SN: No, because they are bloody difficult things to look at. I think Matisse was taking the piss. I swear. I get what he was after. It is like Matisse's chair, but I think people read into that the wrong way.

GT: Do you mean that the comfort wasn't about things that are easy on the eye?

SN: It's about something that one would want to keep you in the chair for a long time. Whenever I read that quote, I always ally it to the Raymond Chandler quote: "She had the kind of smile that he wanted to slip into like a hot, warm bath". And, you know, it's not physical, it's just the poetry of their experience, of what it's like to just be in, and I think that's what Matisse meant. People always envisage Matisse in his later life sat in an armchair and the painting being comfortable. I don't think Matisse's paintings are comfortable at all. In some ways they are more problematic than Picasso's. I still don't get them. I look and look ¾ absolutely exquisite things, but I think he was wanting me to stay and look and sit and linger, in the same way that one does with one's thoughts in an armchair, or with a book.

GT: And is that the intention with these works that you've made?

SN: I'd like them to linger, yes, and I'd like people to probe and look again and again.

GT: And yet your work doesn't linger very long in your studio, and you destroy an awful lot of work.

SN: I just move on. I need space. They're very immediate things to me. And when I move on, I don't think it's destructive, I just move on, and those things don't seem so apparent to me; they're just documents of history.

GT: But many artists are self-consciously creating a catalogue of works and attaching value to everything they make, and by that I mean not just cultural value but also a potential financial value. Are you resisting that?

SN: I'm just not involved in it.

GT: Are you consciously going against it?

SN: Part of me is, but I'm not involved in that world. If I were to be collected and bought, if somebody bought a piece of my work, which people do infrequently, it then takes part in a different kind of transaction. And then if my work were to be in an auction at Christie's, it would take part in another transaction, and then if my work was to be shown in a major museum. These are the currencies I think you're talking about.

GT: I want to challenge you on that, because I think there is an aspect of your practice which is insisting on the process of making and looking as the most important process, not collecting or curating.

SN: There's no challenge. I agree with you. The only thing that makes me happy, in terms of practice, is the making. I'm sure most artists would say this ¾ the building, the creating, the forming, and when you stand in front of a work and are moved by what you've done. The process is so exciting to you that you're actually in that state where you think: "Did I make that? But it's not bullish.

GT: A number of artists are more self-consciously creating a linear narrative around their practice, a story which in many ways sits very easily and comfortably with the art world.

SN: Are you talking about subject matter, or are you talking about their own fictions?

GT: Both. Sometimes they overlap. What's really interesting and uncomfortable about your practice is that it resists those narratives. Even though I'm trying to extrapolate connections and a story, my efforts are constantly frustrated because the works don't conform, they refuse to follow a linear sequential narrative of development.

SN: But you can see things in this exhibition. They're not narrative, but there is an exchange. There are currencies here that are occurring ¾ cloth, fabrics, the found, the built and so on. The assemblage of the chicken wire, the poverty of the wood, the marks left, the marks removed, the marks placed, the marks taken away. Maybe it’s a British thing, the storytelling.

I remember showing with some other artists, and some people walked in and they went, "Is that a such and such?" They saw it straight away not me they saw this person's work and they went, "Is that a…?" And I went, "Wow! What a signature," you know. I would hope that people can tell my work. I hope that people could tell my work through touch, not through narrative or material or subject matter. I hope that people could say, "That touch that that person has is…" well, dare I use the word "unique"? But the touch is an important thing, and there are artists I have always admired who have that touch. I mean, it sounds vain, but I would hope that people could say, "Well, there's something about that, there's something in that work that still has him imbued in it."

GT: I think it does. And it is very much in the physical choice of fabric, in the assemblage of the fabrics, in the modelling of them in the physical sense, but also in the act of forming something new and different out of the objects and materials that you've found and assembled. It comes back again to the very physicality of the process of making. We were talking earlier about the art historian Norbert Lynton, someone who thought the most important thing was spending time with an artist in their studio, looking and talking about work. In recent years, we seem to have lost somewhat our direct engagement with the physicality of work, with the ability to talk to the physical existence and process of making work.

SN: And the place.

GT: And the place. And your work demands it.

SN: This is the forum I want: I want to be with somebody whilst they're looking ¾ it sounds very dramatic, but almost forcing them to look, so that they're sat exactly where you are right now, in front of a wall of green and fabric, so now you can't get away. You're forced to look, and I think that's the experience of the studio. And, you know, this is our potting shed, this is the way we spend our days and whittle away and build and think and sit. But you want people to share in that experience, because it's instrumental in the making and it takes time to be in the studio. It takes time to build the studio in terms of materials and to create the right conditions for making. So this is my place and when the work goes to a gallery that place will change again. In Space Station it's going to be fascinating to be in an ex shop or a gallery, with doors and glass windows and get the opportunity to do that again, change it again. But in here, it's here where we talk, are our most intimate, and we want people to come and engage. And it's happening less and less.

I've been reading recently Lionello Venturi's book on painting. God, it's magnificent! There's a whole section where he talks about the Scrovegni Chapel in Italy and he talks about Giotto's rocks and what it was to be Giotto and paint a rock, and how this was an equivalent for a figure, but it was a framing device too. It's a rock, and Giotto knew what rocks looked like, but these are Giotto's rocks. It's about how it would be to be Giotto, what he's confronting, and how he created this thing. And I just thought: I'd like to create Giotto's rocks, build upon something that is a semi-equivalent for something but might represent something else. And you know, this is where we do it, so the studio is paramount. I really do want people to look. It's the hardest thing to do to get people to look, and I don't know how you do that. I'm lucky in that I think that artists are quite good at looking; we spend a lot of time looking; we get better at it.

I think we've lost a little bit of that sense we all have. And it's no accident that in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries people looked more at one image in their life, for longer. We look at several hundred images a day, but in Renaissance Italy a person sat in the same pew two or three times a week and just looked at that thing, and probably understood it with such resonance and power, and as a communication with God, as a conduit, People devote hours to books; people read a book for several weeks, and they'll give it two hours a day or an hour a day, unlike painting and sculpture. I'd like to draw people in, and the studio is the place where one feels the most comfortable, and strangely enough it's the best place to see work.

GT: I learn the most when I go to a studio.

SN: You know, I learn the most, and I see it here day after day, and maybe two years from now I'll know what these works are about. And it's not hindsight. I have the foresight to make them, but I don't really understand them completely, and that's that little bit of me that's part subconscious that is quite exciting. If you asked me about work ten years ago I could tell you exactly what I was thinking at the time, what I was reading, the way I was voting, who I was with, what I was eating. I could tell you every single thing, every experience of my life. Right now, I haven't got a clue. And that's the hardest thing to explain, that for me there's a little mystery too, and it's the mysterious that I find exciting.

GT: When the development of Bankside power station was proposed for the new Tate Modern, the architect Cedric Price sent in a little model of the Bankside site, and his proposal was that a big glass box should be built over the power plant and that everyone should think about it for a while because ideas and artworks can’t necessarily be understood straight away but require time for reflection. Have we really thought about what a work of art is?

SN: Or how our culture has changed in the last twenty years, how the notion of looking at art has changed, how economics have changed, politics. You're right, and given that 9/11 is probably one of the most profound experiences in our lives, an earth-shattering experience, in the way that [for] our parents the Second World War or maybe the Vietnam War was. Things have changed; the whole world has shifted, and in five years' time religion may shift and change. I don't know how long we go on thinking for, but I'd be happy to look at a glass box with a power station inside it.

GT: And your works are just such an invitation. They're an invitation to stop and think, to reflect.

SN: Yeah, and wonder about the textures and me, to look and wonder: "What is he thinking?" I mean, that sounds a bit flippant, but for people to try and fathom the nonsense of construction or the nonsense of building something that isn't practical. I mean, there's a school being built over here; every day it's disparaging; they've nearly built the school and I'm on my third sculpture. But I want people to think about that. I want them to realise that things are going on outside the studio, but in here there's another thing going on that is different.

Martin Holman

'Passing it on, once more. The hard and soft sides of Stephen Nelson'

'The only thing that makes me happy, in terms of practice, is the making. I’m sure most artists would say this – the building, the creating, the forming, and when you stand in front of a work and are moved by what you’ve done. The process is so exciting to you that you’re actually in that state where you think: “Did I make that?” But it’s not bullish.’

What Stephen Nelson makes is a kind of diary. In fact, the notion of recorded activity, of an archive of gestures made, observations noted and occurrences seen is very strong his work. Most diaries do not see the light of day, and when they do, their revelations either bore the pants off their disconnected readership or they work up our imaginations like a limpet mine biding its time before it blasts from its fragile casing.

Nelson’s objects and drawings relate to this latter effect. Not precisely, you understand, as nothing about what he does strays beyond the perimeter. And that may be the core of its interest: Nelson is the one of the best informed onlookers at work in a London studio. From that vantage point, he makes; he makes up his own mind; he makes some more; and he makes his moves.

That move may be into my territory. Where I am, or where I have found myself, stopping and looking. Looking? No, probably seeing - seeing what Nelson makes me see that is there and that, at the same time, is not but it could be. Then, again, he may destroy what he has made, although the imprint of the events that brought it forth is never lost. It moves forward with him. ‘I just move on. I need space,’ he says. ‘They’re very immediate things to me. And when I move on, I don’t think it’s destructive, I just move on…; they’re just documents of history.’

Whose history? His? Yes, partly, although a curious onlooker never neglects to record how the mega impinges on the micro. Nice mineral, stunning form, but what human cost was on the price tag? A worthwhile diary acquires that scope effortlessly; it is the writer’s first nature. Fanny Burney’s diary was her era; Samuel Pepys was his; and Richard Crossman made a memorial of his (well, actually, his and many others’). I did not know the last three personally, nor live in their times (much); but I’ve read their diaries to reuse what they found – pulled it up to me and passed it on. I do not need to know Stephen Nelson; although he shares my time, his world is different. Nelson once settled in the Horn of Africa; grew up in Liverpool; dived in the Dead Sea; tracked wolves in the Apennine mountains; lived in Rome; brought British artists to Tanzania; crossed America; sailed the Mountains of the Moon; talked with giants.

The last two may not be accurate; in fact, I made them up. The spread of thought that Nelson facilitates allows whimsy as well as igniting much tougher resonances. I am not seeking precision. Because in his objects, their shapes and surfaces, colours and volumes, patterns and patinas, weights and inclinations, and whether they linger on the outside or enquire about the space within, hang from the ceiling, crowd the floor (perhaps hop on a coffee table for extra height), or if they are paper and stick, wire and cloth, bronze or wax, watercolour on paper, or just skid across the wall like a lizard who leaves amulticolour trail in memory of its own angulating tracks, whichever (and they cover all of these, and some), I find that I absorb an extract of another day – or space, or place, or manoeuvre – like hearing this morning’s reading from the Book of the Week on Radio 4. And I make it mine.

Nonetheless, associations with the exotic are no strangers to the work of this British artist. There is ‘exotic’ as in ‘outlandish’, ‘unusual’ and ‘romantically strange’, all of which I find permissible. And there is ‘exotic’ in its ‘ethnographic’ guise which, for me, belongs to the ‘eye of the beholder’ category of detachment, especially if that beholder’s eye is fixed on television, the web or other modern methods of knowing the world from a screen. That is an ‘imported in’, not a ‘given out’. For Nelson, I sense, that ‘brought from a foreign country’ aspect of his practice is purely fact, not wonder; these things exist in the world that is more immediate for him. Strikingly, for a European, there is no ‘-centric’ about his outlook. Cloth that is much-washed, sun-dried, patched and added to, that covers form in what Nelson makes but could cover shoulders, is salient in another sense: it is emotionally cold in space where satellites shrink the globe to an instantaneous click of a mouse. Nelson will not neglect the warm side.

Whereas many artists seize the moment, Nelson passes it on to the next, and to the one beyond that. Communication seems to be chord that is running through the varied manifestations of finding, thinking, handling, assembling, placing, observing, inviting and discarding that are like subtle tugs upon the root of a tooth. It is transmission (even with that word’s viral connotations) in a ‘pass-the-parcel’ aesthetic of regenerated materials: each manoeuvre leaves its thumb print, the grease of the palm like the sticker on a cabin trunk washed up in a thrift shop, but really only in transit with the sensation of an over-night disembarkation. I have never been there, but I metaphorically sniff it and I may as well have been. I care about it now that I can smell it.

Nelson cares; he has an eye for the ‘fine’ that makes his art ‘fine art’, like the gait of a wolf or its socialising ritual. These sculptures are not about travel as in, well, travel, but as in circulation (what blood also does to keep us going); about replenishment, growth, even life-support. Their physicality is their strong suit: it projects making into the viewer’s domain, willing that person to ‘make something of this’, to figure it out. Nelson’s work is made up of ‘possible objects’ rather than sublimated autobiography, and that is a token of their generosity. That physicality appears also to want to extend beyond form to the senses, especially to touch because the hand is the crucible of human activity.

An object of Nelson’s does not stop to consider whether it should stop. Coral does not do this either; instead it accumulates old matter and remakes itself; it grows higher and pushes itself outwards. It pushes itself, taking on new colours and in parts becomes very sharp so that it hurts. You can take a bit to become a souvenir; it finds itself with another who never saw it grow but who is captivated by its form, weight, volume, surface, by the way it falls backwards or tilts to the side. Until it is passed on, maybe reshaped.

Even if I did not know this Stephen Nelson personally I would feel that a sense of myself flows through the things he makes. They pass on to me

July 2008

© Martin Holman 2008